“Nothing that we do that is worthwhile is done alone.” —Mariame Kaba

“Make it as sustainable as you can within your means, but more than anything, share it, build a community around it.” —Mary Annaïse Heglar

The stove in the house I live in—where I cook 2-3 times a day—is nearly the same age as me, and just as moody. I am often frustrated trying to remember its many quirks. There is one level burner, and the rest are some version of uneven: the right side sits higher in the back; the front is titled to the side. When my family and I try to cook, food will often pool in areas with lower elevations. And, as a result, the cooking temperature can also be erratic. It’s imperative to take care while cooking over this old stove. We have to place the pots and cast iron skillets in just the right spot; leave meals to roast or treats to bake to linger a few minutes longer in the oven. The fate of a whole meal depends on this delicate balancing act.

I read a post by Bristol-based printmaker and illustrator, Rosanna Morris about the 6-months she and her family spent living off the grid in yurts during the winter. Morris poetically describes the long, cold days she had to move through to take care of her family, and still do her work. As I read, I remember the walls of the homes I’ve lived in, constructed with different materials—some earthen, some synthetic—each with its own smell and taste. In Bamako, the scent of red clay was always around me, dancing on my tongue, in my nose, and in the food that I ate. The feeling of water saturated the air in Ogata-mura, a small rice-farming village carved out of a once-full lake, surrounded by the Oga sea.

Cooking in these respective places involved a certain set of logistical factors. Family size is one essential consideration. Kitchen space and storage are also important. In both cases, forethought is key: getting to the market, prepping ingredients, and planning meals to limit waste. These are factors that I don’t have to think about and don’t consider often enough. My stove works, all I have to do is turn it on.

The worn kitchen range I tend to will someday collapse, but it does not teeter on the same edge many communities face amid the unfolding story of climate change. In Not Too Late: Changing the Climate Story from Despair to Possibility, writer Mary Annaïse Heglar asks, “What if you broaden your perspective beyond what you can accomplish alone and let yourself see what you could do if you lend your efforts to something bigger?” I appreciate the reframe toward a collective vision—I am Pisces sun, and a partial Lunar eclipse in Pisces is on its way—because for years it was believed that individual, solitary action was the foremost ingredient to mitigate the effects of a rapidly shifting climate, heavily touted through popular media. As much as Nickelodeon influenced my generation to think about the environment, it was short-lived.

An hour north of me, communities are facing food insecurity at disproportionate rates compared to state-wide statistics. This especially impacts brown and black children, many of whom experience school as the sole place where they will reliably be fed at least one meal a day. The quality and significance of school food programs are beginning to shift as advocates work to ensure nutrient density and more culturally relevant meal options. Toledo, and cities around Ohio, are taking a multi-system approach to get food to people who need it. But when it comes to moving the current system away from racist ideologies about who gets to eat, and which communities are subjected to dehumanizing, baseless claims regarding eating, my home state has work to do.

In the small city where I live, I have first-hand experience as a student in the local system, as an urban farmer, and now, as a parent. I also have the privilege of having lived in a rural area in Japan where most of the school food was scratch-cooked, and every student participated in serving and cleaning up after meal time. There, I witnessed a system that is cyclical and generative, the exception contrasted, in some ways, with what children experience in my hometown. I know that responsibility is also on me, as a parent, and now gardener.

Making a meal requires the labor of many people. It is not a singular activity, it was never meant to be. Changing the tide of collective behavior will take the commitment of many. As we begin a new eclipse cycle on the Pisces-Virgo axis, themes of service, health, and change are palpable. What is the physical work required of spiritual dreaming? And who benefits? We’re at a point in the year, in the moment, in the crisis, when we have to choose what to transform, and how to plan for what comes next.

News (and a Question)

I recently asked this question on two other platforms, and the feedback was positive, so I thought I’d ask here: If I were to hold space for a 9-week group for women and femmes who want to transform their relationship with food that would include breathwork, writing, and meditation, would you be interested?

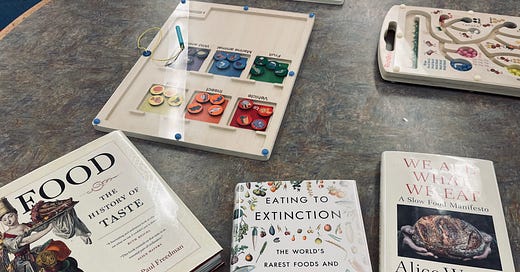

Reading

In addition to finishing up Not Too Late: Changing the Climate Story from Despair to Possibility edited by Rebecca Solnit and Thelma Young Lutunatabua, I am also reading Animal, Vegetable, Junk: A History of Food, from Sustainable to Suicidal, by Mark Bittman.

Listening

This playlist is getting me through a long administrative task list. Maybe it will serve whatever work you’re doing, too: