Dear relatives,

We’ve made it past midsummer. How are you? What pleasures or curiosities have you reveled in?

Last week, while my son and I were out on a wagon ride, we came across (what I believe to be) a family of crows. Their beaks were long and pointed, and their blue-black feathers were slick. There were three, formed auspiciously in a sort of triangle: one on either side and one in front. We approached them slowly and respectfully, taking time to really see each individual bird, and then as a group. The small flock let us get close enough to be seen, so we took our time zooming in and out this way until they positioned themselves for takeoff. We noticed that the sun made their feathers appear iridescent, and through the deep sheen, we witnessed flicks of lavender shine as they flapped their wings, disappearing into the canopy of woodland trees.

The experience with the crows reminded me of two things: a poem that I wrote using birds as a metaphor for grief, and an article that I came across in The Atlantic by Jenny Odell titled “Why Birds Do What They Do.” In the essay, Odell makes a solid case for bird-watching, or as she calls it, “bird-noticing”. She writes, “To observe birds not just as instances but as actors is bird-watching in time, whether I’m observing moment-to-moment decisions or changes across the seasons.” She also highlights the inherent challenges observed through the history of witnessing bird behavior, a realm that intersects philosophy, science, and art. Birds, and other small relatives, process images faster than humans do, which also means their perception of time is in slow motion. I imagine this small fact to be a big reason why Odell and other birders, like conservation ornithologist Drew Lanham, find joy, awe, and humility in watching our winged relatives do their thing. Our worlds are so different from theirs, seeing them reminds us that we are part of a larger story.

I didn’t expect today’s letter to start with a story about crows. Nor did I anticipate the brief dive into the visual experience of birds. As I considered how Anne Lamott’s book Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life would inform this missive, my thoughts geared toward drawing out the technical and practical aspects of the book. The crows had another idea, imagining something different for the fate of this exchange between us. They brought me into a frame of thinking that is poetic and illustrative, demonstrating through their distinctive caw a soundscape that reaches across thresholds, almost dissolving time. This is the precious power of birds. With a newfound appreciation for them, I share Odell’s concern for their survival. “Trying honestly to envision a world in which there are still birds for us to watch means thinking about how bird-watching can never be an idle or apolitical hobby, insofar as I’m watching the lives of others on this imperiled planet where I also live,” she writes.

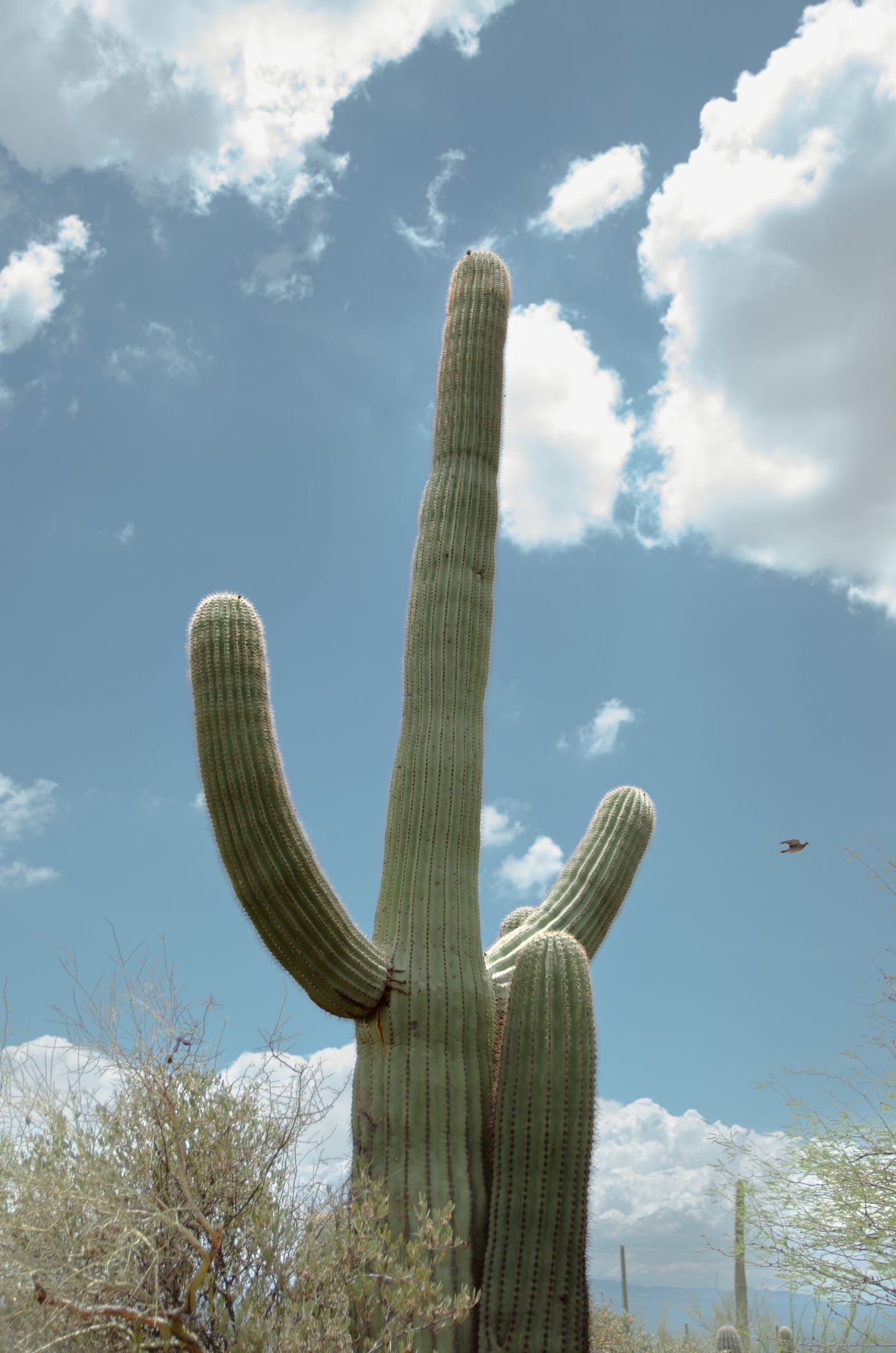

Listening to birds also reminds us to look up into the vast sky we take for granted. Our ancestors knew how to be in relationship with birds, and they were often considered sacred beings representing wisdom and divinity. “Bird sounds reveal the polyrhythms of a living Earth,” writes biologist and author David G. Haskell in an essay for Emergence Magazine. The very air we breathe is the same air that birds live in, and we are undoubtedly tied to their songs and their breath.

I don’t imagine Lamott meant for me to take the birds so literally, but in metaphor, we often find holy cathedrals of meaning; places where the heart-mind can freely wander. She writes, “Writing is about learning to pay attention and to communicate what is going on.” Birds, like writing, can help us reclaim our attention, little by little. In light of this, I thought it would be appropriate to share the poem about grief featuring birds. I jotted down the bones of this poem on a walk with my son. While he napped, my hands quickly typed on the small keyboard of my phone. The words came nearly two years after my father passed, all the while many more lives were slipping away in the midst of the pandemic. As poems always do, this one made the perilous world feel a little more coherent, offering kinship in the form of verse received through the voice of birds. I sense that this is, in part, what Lamott might have been pointing to with her birds: to let yourself be vulnerable and curious enough for the natural world to sing through you.

Relative, I’d love to know: who is singing through you?

With gratitude,

Christian

Listening | Reading | Creating

I’ve been listening to “Doni Doni” by Vieux Farka Touré on repeat. Touré, referred to as “the Hendrix of the Sahara” is the son of the legendary Malian guitarist Ali Farka Touré, whom, by some great fortune, I had the opportunity to meet while I was an art student in Bamako. Speaking of cosmic occurrences, I received a copy of Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden, by Camille T. Dungy, from a recent giveaway hosted by Black Girl Environmentalist. This was my first experience winning a giveaway, and I am excited to start reading. As far as creativity goes, I am still working towards completing a few projects. Little by little they are taking shape, taking flight.

Love everything about this one!